LTCOL GREG SHANNON, OAM (RET’D)

It is fair to say that most battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment that served in Vietnam had one operation or battle that for various reasons became indelibly stamped on everyone’s memory. Some operations became enshrined in Australia’s military history and have been commemorated as battle honours on the Regiment’s colours ever since. To name but three, for 6RAR it is Long Tan; for 1RAR and 3 RAR, it is Coral and Balmoral and for 5RAR, it is Binh Ba; all names which add lustre to the Regiment’s already proud fighting record.

But although most battles were neither widely known nor proudly quoted, they are nonetheless significant to those who fought in them. For the soldiers of 4RAR/NZ (ANZAC) Battalion, in 1971, it was Operation Ivanhoe, and the Battle of Nui Lé, particularly the events of 21 September, that became the focal point of the battalion’s second tour; 50 years ago, this year, and the last major battle fought by Australian and New Zealand troops in the Vietnam War. I was the battalion signals officer at that time.

At the outset, it is important to place on record the misgivings held by our commanding officer, the late Major General (at the time LTCOL) Jim Hughes, AO, DSO, MC, over many years and particularly in the months prior to his untimely death in August 2016. He was of the view there were many in the Australian military community that thought 4 RAR, on its second tour, had very little to do. The battalions that went before us had done it all. We were just there for a bit of a ‘jolly’! Those of us, however, on the second tour know that this was very far from reality. The battalion was heavily committed continuously for the whole period of the shortened tour in 1971 and very much made a mark and upheld in every way the reputation of the Australian fighting soldier and the traditions of The Royal Australian Regiment. I would submit that the Battle of Nui Lé ranks up there with other maybe better-known battles involving Australian soldiers in the Vietnam War.

Another matter that played on his mind for many years, from an operational perspective, was the absence of the Centurion battle tanks at the time of the battle. It took him many years to identify the person who had made the premature and ill-informed decision to withdraw the tanks from the order of battle in July 1971 for all the wrong reasons. There is no doubt that they would have made a significant difference had they been available rather than being on the high seas enroute back to Australia.

It is also useful to put Operation Ivanhoe into some strategic context. Exactly a month prior to the day that the operation commenced, on 18 August 1971, the then Prime Minister of Australia, William McMahon announced in parliament “that the combat role which Australia took up over 6 years previously is soon to be completed.” Further, he announced “most of the combat elements will be home in Australia by Christmas 1971.” This news was received with some excitement by our troops and was reported variously in the Australian media. Although reports to the effect that there were no Australian troops still actively engaged in combat were viewed a tad incredulously. It certainly was not the case and as events unfolded the battle drew direct political intervention when the same Prime Minister passed a message to the Commander AFV, General Don Dunstan “expressing concern about incurring further casualties at such a sensitive time!” This was actually during the battle when the battalion was fully committed. Fortunately, the task force commander Brigadier (later Major General) Bruce McDonald had the foresight not to pass on this snippet to the CO. In politics, some things never change!

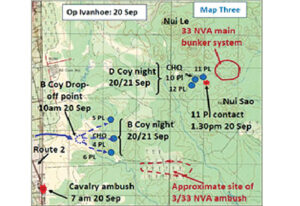

In early September 1971, ‘people-sniffer’ missions flown to the east of Nui Lé and Nui Sao, the two largest features in the northeast of Phuóc Tuy Province, indicated the presence of an unidentified enemy force. (‘People-sniffers’ were helicopter mounted personnel detectors that measured the effluents unique to humans.) Intelligence assessments were strongly of the opinion that these missions revealed enemy elements that were probably our “old friends” the 33 North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Regiment; specifically, their regimental headquarters, and the 2nd and 3rd battalions. Their total strength was around 800 all ranks. It was assessed that they were probably back in the province to establish a base there for operations against the northern villages and outposts along Route 2.

So, Operation Ivanhoe was mounted to find and confront 33 NVA Regiment; specifically, 4 RAR’s mission was to ‘redeploy east of Route 2 and locate 33 NVA Regiment’.

The CO’s concept of operations was to deploy three rifle companies into the north of the Area of Operations (‘AO’) between the suspected locations of the 33rd and their probable sanctuaries in Long Khanh Province to the north of Phuóc Tuy province. The companies would then search from north to south. Support Company would be deployed in block and ambush positions north of the searching companies in the Courtenay Rubber Plantation. 3 RAR would be operating to their northeast. Meanwhile 1 Troop A Squadron, 3 Cav Regt, again under operational control of the battalion, was to maintain a presence west of Route 2 and north of the province border in Long Khanh Province and would ambush in those areas by night.

This meant that the enemy would either have to fight their way north through the rifle companies to escape into Long Khanh or alternatively go south to evade the companies before turning north and heading for the border. In either case, if the enemy got clear of the rifle companies, they would still have to fight their way through Support Company, 1 Troop and the 3 RAR blocking positions before gaining the sanctuary of Long Khanh. It was a simple plan and would put maximum pressure on the enemy while leaving the CO ample opportunity to redeploy Support Company and 1 Troop if necessary.

Although the operation was scheduled to begin at midnight on 18-19 September, there would be of necessity some coming and going within the AO for the first two days. Victor Company (our Kiwi brothers!) was back in Nui Dat as Task Force Ready Reaction Force and would not be released back to the Battalion until 22 September. C Company would be taken to Nui Dat for R & C (rest and convalescence) leave at 1600hr on 19 September and would not be available again until 24 September. And B Company was to be redeployed from Nui Dat into their AO four kilometres southwest of D Company but not until 1000hr on 20 September. D Company, however, which had been in the AO at the end of Operation North Ward, would begin their search at 0800hr on 19 September. The battalion headquarters was located on Courtenay Hill, on Route 2 at the northern most part of Phuóc Tuy Province.

In pactical terms this meant that the CO only had D Company clear of any other commitments in the AO. Consequently, Brigadier McDonald placed D Company 3RAR under operational control of 4 RAR from 1000hr on 19 September, and they were inserted into their AO just east of the Courtenay Rubber Plantation.

The operation, however, began tragically. Due to some confusion over two radio messages from Battalion Headquarters (BHQ), D company propped twice to decode the messages and, shortly after they set off again two of the D company platoons engaged each other. Sadly, a reinforcement, Private Maxwell Rhodes, who had only just joined the company, (a national serviceman who had deferred his national service obligation to complete a university degree), was accidently shot, and killed. The messages, however, which precipitated this dreadful accident, were very relevant. Intelligence reports indicated that D company was within 500 metres of either one or two enemy radio sets. The Officer Commanding (OC) D company, Major Jerry Taylor, applied a worst-case analysis and interpreted this as potentially two enemy battalions given that radios sets were rare below battalion level. As a result, he decided to keep the company more concentrated than usual.

There were no other incidents that day, although earlier in the morning, the 626 Regional Forces Company outpost on Route 2 received an attack by fire from a 75-millimetre Recoilless Rifle and 82-millimetre mortar rounds. 33rd NVA Regiment held both these types of weapons. Tracks from the firing points led to the east towards the Nui Sao, which was south-east of Nui Lé .

Early on the following day, 20 September, 4 APCs from 1 Troop 3 Cav Regt were ambushed along Route 2 between the village of Xa Bang and the RF company outpost by approximately 20 enemy employing rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and small arms fire. A swift counterattack resulted in one enemy soldier being killed. He carried no identification but was well armed. The ambush position was around 150 metres long and set 250 to 300 metres back from the road. Sign indicated that weapon pits and sleeping bays found had been occupied during the night.

A POW, captured by 3 Cavalry Brigade (US) in November 1971, who had been an assistant platoon commander with C9 company of the 3rd Battalion, 33 NVA Regt revealed to interrogators that the original plan had been to lure 1st Australian Task Force units into a prepared ambush, east of Route 2. (This also gave some credibility to the rumour that the NVA regiment had deployed back into Phuóc Tuy Province to give the Australians a ‘bloody nose’ before we went home!)

The attack on the regional force outpost on 19 September and the ambush of the APCs the following day in the same area were the ‘bait’ in an attempt to lure an infantry/armoured reaction force east from the area along a logging track (ambushed by the 3rd Battalion) and into a bunker complex further to the northeast near Nui Sao, where the 2nd Battalion and the RHQ occupied defences in depth.

At around 1330hr, on the 20 September, Gary McKay’s 11 Platoon engaged a fifteen-man enemy group about a kilometre northeast of Nui Sao. 11 Platoon opened fire; killing one enemy soldier instantly. The enemy deployed speedily and returned rapid fire but were apparently ordered to withdraw by their commander. Artillery was fired onto their withdrawal route, and a Pink Team, (consisting of a light observation helicopter (or “Loach”) and one or two Cobra gunships) assisted. The Cobra gunship was employed to pursue them and opened fire, but without discernible results. Shortly after, 10 Platoon had a brief firefight with, probably, the same group as it withdrew, but there were no casualties on either side. (The rather beguiling name ‘Pink Team’ belies somewhat the actual role of these US units. They were better described as ‘hunter killer’ teams. The Loach, a Hughes OH-6 Cayuse, would fly at tree top level trying to tempt the enemy into firing at them and when they did the Loach would mark a target and a Cobra Gunship would roll in and attack the enemy. They were a very formidable weapon platform.)

When 11 Platoon searched the contact area, they located one enemy KIA and an AK47, a pack and two Chicom (Chinese Communist) grenades. A follow-up failed to locate any more enemy and the platoon formed a night defensive position (NDP) in the area. A second enemy KIA was located the next day. It was noted at the time of the contact that the enemy were wearing dark olive-green uniforms and navigating with maps and compasses. This was unusual and further confirmed that we were up against NVA soldiers, the 33rd NVA regiment.

There was an uneasy feeling throughout the battalion on 19 and 20 September 1971!

On the morning of 21 September, 12 platoon located a separate branch of the track from the previous day and suddenly they were engaged by RPGs and small arms fire. During the action 12 platoon lost one soldier, Pte Jimmy Duff, when an RPG exploded on the tree that he was using as cover. Four other members of the platoon were wounded, including the platoon commander, Graham Spinkston. 12 platoon had come up against what was later established to be the western most bunker system of a four system complex, large enough (with 24 completed bunkers with 15 prepared bunker sites) to accommodate the 2nd battalion, 33rd NVA Regt. (Spinkston was actually hit by two bullets, one in his leg and the second was stopped by a thick paperback novel, “The Taste of Courage”, in one of his basic pouches! The book is now on display at the Australian War Memorial.)

At the same time 11 platoon was attacked by a large enemy force from another part of the same bunker system. But with support from both US and Australian gunships, and hard bombs and napalm from US Phantom jets, 11 and 12 platoons were able to break contact and re-join the company. For the next 3 hours the enemy position was pounded with repeated air and artillery strikes. Over 2000 artillery rounds from 104 Battery pounded the position. It was quite a spectacle to watch from the safety of Courtenay Hill.

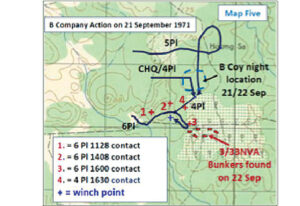

Meanwhile B company, having been inserted by APCs on the morning of the 20th, was generally moving east and south, dispersed as single platoons. They had a few minor contacts and saw sign that indicated somewhat larger enemy parties. Then at 1130 hr OC 6 platoon, 2LT Dan McDaniel, reported the discovery of a telephone wire and had begun to follow it. As they were proceeding, two enemy approached from the northeast and were engaged. One was killed and the other withdrew northeast. The enemy appeared to have been checking the wire.

A few minutes later, LT Simon Willis’s 5 platoon reported that they had found fresh foot tracks heading east and south, about 1500 metres northeast of 6 platoon. B company was now moving carefully because they could hear D company’s battle off to the northeast, and they had been listening to progress of the battle over the battalion command net. Now their own platoons were making contact and finding sign, and at 1130hr, following searches of enemy bodies and their equipment, Major Bob Hogarth was able to confirm to the battalion command post (CP) back on Courtenay Hill that his company was in contact with NVA troops. Although no unit identification was possible, the enemy could only be the 33rd NVA regiment.

2LT McDaniel’s platoon continued to follow the telephone wire that had been discovered during their previous contact, and saw an enemy soldier rolling it up. When they engaged him, he cut the wire and withdrew east. 6 platoon continued to follow the track made by the enemy and at 1600hr commenced a recce for their night location. The recce party then observed enemy to their east, southeast and north. They engaged them and started to withdraw only to be engaged by SA fire and a 60mm mortar north of their position. 6 platoon sustained considerable casualties from the mortar rounds’ shrapnel, about half the platoon 15 in total, (including 2LT McDaniel, the platoon commander!). 4 platoon (LT Ian Ballantyne) was sent to their assistance to endeavour to hit the enemy from the north. (McDaniel had assisted with the evacuation of his casualties and did not know he had been wounded; it was only during the night that what he thought was his back sweating turned out to be next morning, when he could see, blood from shrapnel wounds. He was evacuated a short time later to the field hospital at Vung Tau.)

The battalion was now heavily committed in two locations four kilometres apart!

Notes:

- 6 platoon, following a telephone cable, engaged by sentries, killing one.

- 6 platoon continues following the cable and contacts one more enemy soldier.

- 6 platoon recon group engaged by enemy and receives 60mm mortar fire wounding 15 men including the platoon commander 2LT McDaniel.

- 4 platoon, LT Ballantyne despatched to assist 6 platoon contacted several small groups of enemy.

+ = Winch Point.

Back at D company, around 1500 hours the company commander Major Jerry Taylor, having formulated a plan for a company attack, ordered the company to shake out into attack formation. 12 platoon on the left, company headquarters (CHQ) centre rear, 11 platoon right flank. 10 platoon was to remain at what was known as the ‘Winch Point’, providing a firm base and reserve. Around this time too, just as the company attack was commencing, there were reports from pilots that the enemy appeared to be withdrawing in large numbers.

Notes:

- 11 platoon and 12 platoon following track system.

- 12 platoon recon group engaged Pte Duff killed by an RPG round: several wounded including platoon commander, 2LT Spinkston.

- D company concentrates at Winch Point on order of Major Taylor.

- D company advances in assault formation.

- 11 platoon receives intense fire form the front and flanks and takes heavy casualties.

- Company withdraws to the winch point secured by 10 platoon.

- D company moves 400 metres south and consolidates into a defensive position.

- Enemy follows up on the company.

- The company has inadvertently deployed against another bunker system.

However, within minutes of the move forward, the company came under withering fire from skilfully sighted and mutually supporting bunkers into camouflaged fire lanes. Delta company, all 90 of them, had encountered the 2nd battalion of 33 NVA Regiment – all 300 of them!!!

Two of 11 platoon’s machine gun teams were hit with a tempest of automatic fire. The two machine gunners were caught in fire lanes, Private Keith Kingston-Powell was killed instantly and Private Ralph Niblett on the other gun was mortally wounded and died a short time later. As the number twos on the guns, Privates Brian Beilken and Rod Sprigg, went forward to take over from their shot mates, they too were caught in the fire lanes and were both killed instantly. After about three hours of fighting, the company just couldn’t breach the system and light was fading. The company was ordered to pull back, leaving their packs and their dead mates behind, to a night defensive position (NDP) secured by 10 platoon. But the NVA was not finished and swarmed out of the bunkers and launched a counterattack. The two platoons commenced fire and movement rearwards to break contact. The enemy just kept coming. Each platoon continued withdrawing in heavy contact. Meanwhile, 10 platoon was moving to secure the Winch Point and they were engaged by what was discovered later to be the regimental headquarters of the 33rd and the 3rd battalion in another bunker complex. This complex also had sniper posts high up in the jungle canopy.

The company was virtually surrounded and jammed up against this further bunker system. 11 and 12 platoons managed to fight back to 10 platoon and CHQ and the company formed a sort of all-round defence measuring only about 35 metres across. The 2nd battalion continued its assault in waves of troops. The regimental HQ and 3rd battalion were pouring fire into the position from above.

The company was fast running out of ammunition and had little protection. There was every chance they were about to be overrun. Because of the proximity of the enemy the company could not use close air support, so Jerry Taylor made the decision to call for ‘danger close’ artillery fire. And the gunners of 104 Battery made the difference, but the noise from the artillery bombardment, combined with the small arms fire was deafening. So much so that the Jerry couldn’t talk to his artillery forward observer, Lieutenant Greg Gilbert who was no more than 10 metres away. Without comms – no guns! No guns and there was a fair chance that the company would be overrun!! I was sent airborne in the CO’s Kiowa helicopter and managed to set the chopper’s two FM radios onto automatic retransmission mode so the OC could talk to the forward observer (FO), and the FO could talk to the guns. (The helicopter pilot, 2LT John Sonneveld flew for 11 hours non-stop that day, save for refuelling and comfort breaks. He was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). I have reflected over the intervening years how lucky we were that the enemy did not or could not engage the helicopter with their 12.7 mm anti-aircraft machine guns!)

Amazingly, as he couldn’t turn on a torch to see his map, Gilbert relied on his memory of grid references and estimations of the distances they had travelled to adjust the fire. Every time the radio crackled, the enemy directed fire into Coy HQ putting the FO and therefore the whole company in danger. The last Australian casualty that night was the 11-platoon commander, 2LT Gary McKay who was severely wounded. McKay was dragged back into CHQ and with the Regimental Medical Officer (RMO), CAPT Paul Trevillian in Nui Dat relaying treatment instructions over the radio to company medic Cpl Mick O’Sullivan; McKay’s life was saved. Once again CHQ came under fire during these radio transmissions. (Mick O’Sullivan, who had been previously awarded the Military Medal for dedicated and professional service under fire, continued applying his professional skills. Gary McKay survived and was awarded the Military Cross.)

The enemy attack went on till nearly midnight, and then suddenly they started to withdraw, and as it turned out, taking most of their dead and their wounded away with them. The next morning, the enemy had gone. They had worked frantically throughout the hours of darkness to evacuate their casualties and withdraw through our blocking forces along prepared tracks which were subsequently located by elements of the battalion searching the bunker area near the Nui Sao.

The construction of a bunker complex near Nui Sao, the cutting of good tracks to facilitate rapid redeployment of NVA units in the Route 2/Nui Sao area and the detailed planning that was involved in the attempted ambush of an Australian force, indicated that 33 NVA Regt intended to establish a base for future operations in that area of Phuóc Tuy province. The final paragraph of the Ivanhoe after action report says: “There is no doubt that the quick retaliatory reaction by the APCs of 1 Troop when ambushed on 20 September and the aggressive action of B and D companies, with plentiful close air and artillery support on 21 September 1971, (during this last major battle fought by Australian troops), were responsible for forcing the NVA to abandon their efforts (which had been considerable) to harass the District, and to return to more secure surroundings north of the Phuóc Tuy Province boundary”.

There is also little doubt that, had it not been for fire support from 104 Battery and Greg Gilbert’s skills in calculating his position without being able to consult his map, and his subsequent corrections which kept the fire moving about the perimeter; and the splendid commitment of the artillerymen at the gun positions, D Company might well have come under a coordinated attack on the night of 21 September. One can only speculate what the outcome of that attack might have been. It was a very near thing.

The cost was high 5 Australian killed in action (KIA) and 30 wounded in action (WIA). 14 enemy bodies were recovered. Many more, as was NVA practice, were taken from the battlefield.

(There is an interesting and ironic twist to this story. Many readers will recall, or have read of, the exploits of the US 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment at the Battle of Ia Drang in the central highlands of South Vietnam that took place on November 14–15, 1965 at Landing Zone (LZ) X-Ray. The battle was regarded as the first major battle of the Vietnam War. Details of battle were recounted by the CO at the time, LTCOL (later LTGEN) Hal Moore in his book on the battle, “We Were Soldiers Once… and Young”. The battle was portrayed in the 2002 movie, ‘We Were Soldiers’, starring Mel Gibson. Who was the enemy at the Battle of Ia Drang? None other than the 33rd NVA Regiment!) Déjà vu!!

In preparing this account of the Battle of Nui Lei on 21 September 1971, I must acknowledge these are not solely my words but rather they are an amalgam derived from four particular written works. First, from the incisive book, ‘Last Out’ written by Jerry Taylor, who was awarded the Military Cross for his leadership during the tour; the book of the tour, ‘The Fighting Fourth’, which showcased the battalion’s efforts in 1971, prepared and edited by Bob Sayce, CSC, the battalion’s Intelligence Officer and Mike O’Neill, the battalion’s transport officer; Gary McKay’s ‘In Good Company’, and Warren Dowell, the D company support section commander at the Battle of Nui Le, who gave a wonderful personal account of the battle at a commemorative ceremony and unveiling of a plaque in memory of Bob Hann, CQMS D company in 1971, at the Bribie Island RSL on 21 September 2016. Without their words, I would not have been able to put this together.

The maps are courtesy of LTCOL (Ret’d) Fred Fairhead’s book ‘A Duty Done’ (2nd Edition), ‘A summary of operations by the Royal Australian Regiment in the Vietnam War 1965-1972’.

DUTY FIRST!

Postscript:

- Sadly, Jerry Taylor passed away suddenly on Saturday, 18 November 2017.

- On 06 February 2018, Lieutenant Colonel Gregory Vivian Gilbert (Ret’d) was awarded a belated Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) in recognition of his skills and courage during the battle. At the time his superiors opined that he was just doing his job!